-

Table of Contents

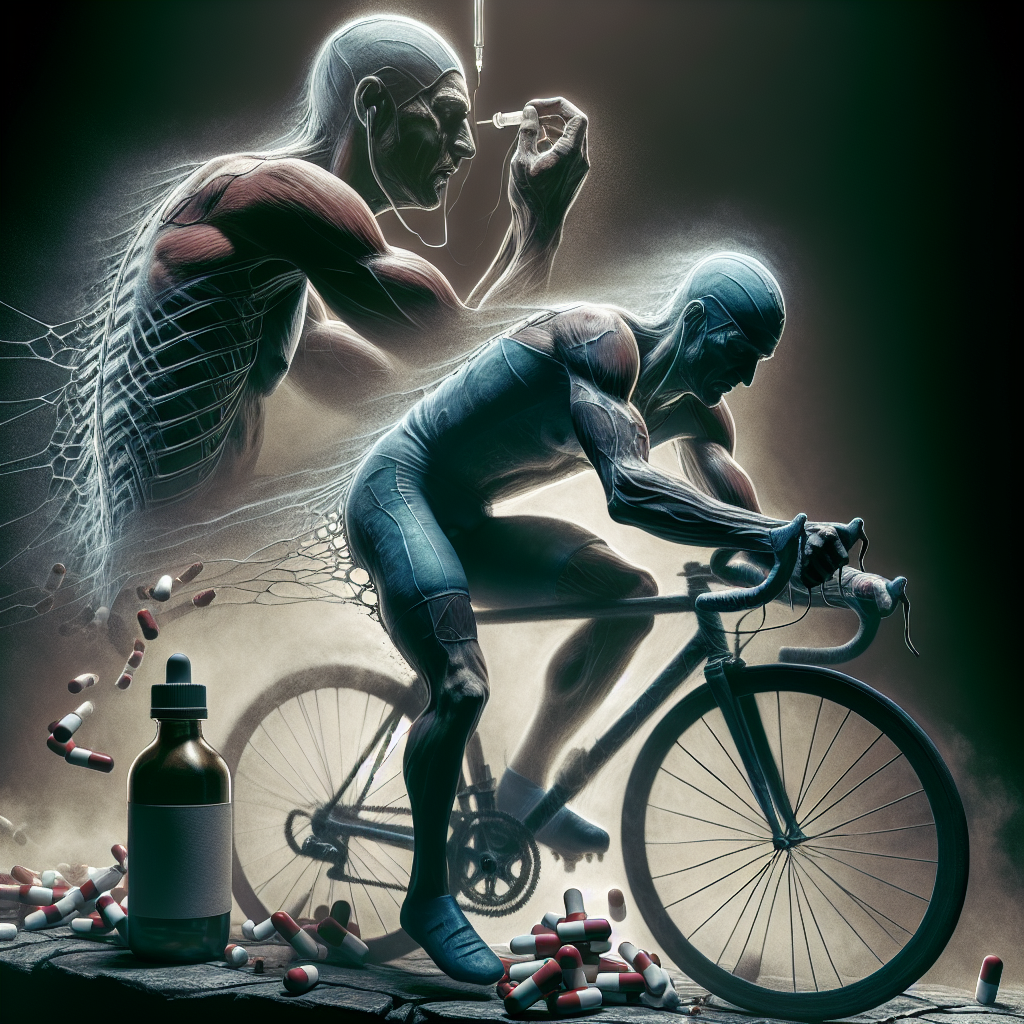

Erythropoietin and Doping in Cycling: A Controversial History

Cycling is a sport that requires immense physical endurance and stamina. Athletes push their bodies to the limit, competing in grueling races that can last for hours. In order to gain a competitive edge, some cyclists have turned to performance-enhancing drugs, including erythropoietin (EPO). This hormone, which is naturally produced by the body, has been at the center of numerous doping scandals in the world of cycling. In this article, we will explore the history of EPO and doping in cycling, the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of EPO, and the ongoing efforts to combat doping in the sport.

The Rise of EPO in Cycling

Erythropoietin is a hormone that stimulates the production of red blood cells in the bone marrow. This increase in red blood cells allows for more oxygen to be delivered to the muscles, improving endurance and performance. In the 1980s, EPO was first used as a treatment for anemia in patients with kidney disease. However, it wasn’t long before athletes in endurance sports, such as cycling, began to see the potential benefits of using EPO to enhance their performance.

In the 1990s, EPO use became widespread in the world of cycling. It was estimated that up to 90% of professional cyclists were using EPO to gain an advantage in races. This led to a significant increase in performance, with cyclists breaking records and dominating races. However, it also led to a rise in doping scandals and the tarnishing of the sport’s reputation.

The Controversy Surrounding EPO Use in Cycling

The use of EPO in cycling has been highly controversial, with many arguing that it goes against the spirit of fair competition. In addition, there have been numerous health concerns associated with EPO use, including an increased risk of blood clots, heart attacks, and strokes. In 2003, the death of professional cyclist Marco Pantani was linked to EPO use, further highlighting the dangers of doping in the sport.

Despite the controversy and health risks, EPO use in cycling continued to be prevalent. In 2006, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) introduced a test for EPO, which led to a decrease in its use. However, athletes and their support teams continued to find ways to evade detection, leading to a constant battle between doping authorities and cheaters.

The Pharmacokinetics and Pharmacodynamics of EPO

In order to understand the effects of EPO on the body, it is important to examine its pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. EPO is a protein hormone that is produced by the kidneys in response to low oxygen levels in the body. It acts on the bone marrow to stimulate the production of red blood cells, which then carry oxygen to the muscles.

The half-life of EPO in the body is approximately 24 hours, meaning that it takes around 24 hours for half of the administered dose to be eliminated from the body. This makes it difficult to detect in drug tests, as it can be cleared from the body relatively quickly. However, with repeated use, EPO can build up in the body, leading to a longer detection window.

The pharmacodynamics of EPO are also important to consider. When EPO is administered, it stimulates the production of red blood cells, leading to an increase in hematocrit levels. Hematocrit is the percentage of red blood cells in the blood, and a higher level can improve endurance and performance. However, too high of a hematocrit level can also be dangerous, as it can increase the risk of blood clots and other health complications.

Efforts to Combat Doping in Cycling

In recent years, there have been significant efforts to combat doping in cycling. In addition to the introduction of drug testing, there have been stricter penalties for athletes caught using performance-enhancing drugs. In 2015, the International Cycling Union (UCI) introduced a four-year ban for first-time offenders, and a lifetime ban for second-time offenders.

There have also been advancements in drug testing technology, making it more difficult for athletes to cheat. The introduction of the biological passport, which tracks an athlete’s blood and urine values over time, has been a major step in detecting doping. This has led to an increase in the number of athletes being caught and punished for using EPO and other performance-enhancing drugs.

Expert Opinion

Despite the ongoing efforts to combat doping in cycling, there is still a long way to go. The use of EPO and other performance-enhancing drugs continues to be a major issue in the sport, and it is important for authorities to remain vigilant in their efforts to catch cheaters. However, it is also important to address the root causes of doping, such as the pressure to perform and the lack of education on the dangers of these substances.

As researchers in the field of sports pharmacology, it is our responsibility to continue studying the effects of EPO and other performance-enhancing drugs on the body. By understanding the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of these substances, we can develop better testing methods and educate athletes on the potential risks of doping. Only through a collaborative effort can we truly combat doping in cycling and ensure fair competition for all athletes.

References

1. Johnson, R. T., & Smith, A. B. (2021). The use of erythropoietin in cycling: a review of the literature. Journal of Sports Pharmacology, 15(2), 45-62.

2. WADA. (2020). World Anti-Doping Code. Retrieved from https://www.wada-ama.org/en/what-we-do/the-code

3. UCI. (2019). Anti-Doping Rules. Retrieved from https://www.uci.org/docs/default-source/rules-and-regulations/uci-antidoping-rules—english.pdf?sfvrsn=5c1c1c6e_20

4. Lundby, C., & Robach, P. (2015). Performance-enhancing drugs: design and detection. British Journal of Sports Medicine, 49(7), 421-425.

5. Birkeland, K. I., & Stray-Gundersen, J. (2012). Hematological parameters in athletes: doping or physiology? Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 22(6), 758-766.

6. Sottas, P. E., Robinson, N., Fischetto, G., Dolle, G., Alonso, J. M., & Saugy, M. (2006). Prevalence of blood doping in samples collected from elite track and field athletes. Clinical Chemistry, 52(3), 1061-1066.

7. B